Russian threat? What Russian threat?

If you are worried about global stability or whether Europe could stand alone against Russia without US forces as a backstop, this analysis will help you sleep more peacefully. (Unless of course you are worried about a lunatic in Moscow pulling a nuclear trigger when his dreams of empire collapse under the weight of their own improbability ... because sorry, that could still happen.)

If long articles aren't your thing, just scan the bolded bits.

As Russia’s war in Ukraine grinds on, Western Europe has grown increasingly anxious about its own security. Politicians warn of a resurgent Russian military menace at NATO’s doorstep, urging higher defense budgets and vigilance.

But a close analysis of military balance, economic strength, and battlefield performance suggests Western Europe has little to fear from Moscow – at least for the next ten years.

NATO’s European members (even without U.S. or U.K. support) far outmatch Russia in conventional air, land, and sea power, with more modern equipment and better-trained forces.

Russia’s arsenal, by contrast, relies on aging Soviet-era platforms that have been depleted and exposed as deficient in Ukraine. Outside of a heavy investment in drones – an area where Russia has innovated out of necessity – Moscow has few advantages, and none that would enable it to overcome NATO.

Western Europe’s economies and defense industries eclipse Russia’s, meaning it can sustain any arms race that Russia attempts. Meanwhile, the Kremlin’s failures in Ukraine, from logistical breakdowns to inability to capture new territory, demonstrate profound weaknesses.

So why, then, do some European leaders continue to paint Russia as an imminent threat? Domestic politics and economic motives play a role: the specter of the “Russian bear” helps justify major defense spending, bolster industry, and rally public support.

Let's look at each of these factors in depth – from comparative military strength to political posturing – the realities show that Western Europe is secure against Russian aggression for the foreseeable future.

NATO Europe vs. Russia: Conventional Military Strength

Air, Land, and Sea Power: By any measure, the combined military might of NATO’s European members vastly exceeds Russia’s. Even excluding the United States and U.K., continental NATO Europe fields a “powerful, and modern fighting force” that is quantitatively and qualitatively superior. In terms of manpower, European NATO countries collectively have over 700,000 more active troops than Russia (roughly 1.8 million vs. 1.1 million), giving them a clear personnel advantage. This gap alone exceeds the total Russian troops currently deployed in Ukraine, underscoring how outmatched Russia would be in a broader conflict.

When comparing arsenals, Western Europe’s edge is even more pronounced. Across five key categories of conventional weaponry – from tanks and armored vehicles to artillery, helicopters, and combat aircraft – NATO countries possess not only greater numbers but also “more modern weapons” than Russia. For example, European Union members together deploy almostdouble the number of main battle tanks that Russia does. As of 2023, the EU’s tank fleet outnumbered Russia’s by roughly 1,860 tanks (a 93% advantage).

Likewise in the air, NATO Europe operates a large fleet of advanced fighters and strike aircraft (Eurofighter Typhoons, Rafales, F-35s, etc.), whereas Russia’s air force relies on smaller numbers of older Soviet-legacy jets. Prior to the Ukraine war, Russia had under 5,000 military aircraft of all types compared to NATO’s 22,000+. In a conflict, NATO’s European air forces – designed for high-tech joint operations to blind and dismantle an adversary – would be poised to swiftly establish air superiority. As Al Jazeera’s defense analysis concludes, the “quality of NATO’s troops is far better in terms of training and equipment,” and with its integrated command and cutting-edge technology, NATO would “quickly prevail in any conventional war against Russia”.

At sea, Russia similarly cannot match the naval power of Western Europe. Russia’s navy, while still possessing some capable submarines and legacy Soviet-era ships, is limited in reach and largely confined to regional waters. It has one aging aircraft carrier (permanently docked for 'repairs') and a handful of major surface combatants – some of which have been lost or damaged in the current war. By contrast, NATO Europe boasts dozens of modern frigates, destroyers, submarines, and even aircraft carriers (France’s Charles de Gaulle and others in Italy and Spain, not counting the two UK carriers). In raw numbers, Russia has about 339 naval ships of corvette size or above versus NATO’s 1,143 – a threefold disadvantage. European fleets patrol the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Baltic with highly advanced warships and benefit from decades of interoperability exercises. In any direct clash, Russia’s navy would be bottled up and outgunned by European naval task forces.

In short, across traditional domains – air, ground, and sea – Western Europe’s militaries outweigh and outclass Russia’s by a wide margin. Even without U.S. involvement, NATO Europe’s collective capability is “formidable” and more than sufficient to deter or defeat Russian aggression. The alliance’s strength lies not only in numbers but in superior training, logistics, and the ability to coordinate as a unified force. Decades of joint exercises have created a level of interoperability and trust that the Russian military, with its brittle top-down command, cannot hope to match. As one analysis put it, NATO’s technological sophistication and integrated command amplifies its effectiveness, whereas Russia’s forces – as currently constituted – would face overwhelming odds.

Pride of the Russian fleet, the Admiral Kuznetzov, in dry dock since 2017. A rare photo where it isn't on fire due to welding mishaps, and the dry dock is still dry (it sunk in 2018).

Cyber Warfare: Resilience vs. Russian Aggression

Cyber warfare is one domain where Russia has aggressively probed for weaknesses, yet it remains an area of concern rather than a decisive Russian advantage. Moscow has a track record of using cyber attacks and information warfare against Western targets – from hacking government networks to attacking critical infrastructure. Indeed, British officials have warned that Russia is “exceptionally aggressive and reckless in the cyber realm,” and is prepared to launch cyberattacks that could temporarily cut power for millions. Notably, a Russian state-aligned operation in early 2022 sabotaged the Viasat satellite network in Ukraine, disrupting communications across Europe. These incidents underscore that the Kremlin views cyber as a theater of conflict where it can harass NATO countries below the threshold of open war.

However, Western Europe has significantly bolstered its cyber defenses and resilience in recent years. NATO and EU members have invested in hardened networks, information-sharing, and rapid response teams to counter malign cyber activity. For example, NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Estonia and various national cyber commands continually study Russian tactics and strengthen defensive measures. Western intelligence services have also improved at detecting and attributing Russian cyber operations, enabling timely sanctions or countermeasures when attacks occur. While no system is foolproof, the outcome of Russian cyber aggression so far has been inconvenience and espionage – not the kind of catastrophic infrastructure failure that could alter the balance of power. As one NATO cyber expert put it, Moscow’s hackers can annoy and disrupt, but they cannot “interpret events and make decisions” for NATO leaders, let alone hold territory. In a shooting war, cyber strikes would be met with cyber counter-attacks and potentially even kinetic retaliation against command centers. Western nations also maintain formidable (if largely classified) offensive cyber capabilities of their own, which serve as a quiet deterrent.

The bottom line: Russia’s cyber warfare can be dangerous and is taken seriously – no one in Europe “underestimates the Russian cyber-threat to NATO” – yet it does not provide Moscow with a war-winning edge. European societies have shown resilience against disinformation and hacking campaigns, and their militaries train to “fight through” cyber disruptions. A cyber attack alone cannot conquer cities or break NATO’s mutual defense resolve. At most, it would be one front in a larger conflict, and one that Western Europe is increasingly ready to manage.

Why haven't I written a Future War style novel or series set in Europe? Because I only look 10-20 years ahead and honestly, I see no plausible scenario for a Russia v NATO conflict in Europe in that timeframe. There are plenty of other more likely conflicts in these novels:

https://www.amazon.com/stores/FX-Holden/author/B07J47L7KB

Space Capabilities: Russia’s Declining Edge

Space is another arena often cited in discussions of Russia’s power, given Moscow’s long history in rocketry and satellites. In Soviet times and until recently, Russia was regarded as a leading space power – launching cosmonauts, operating spy satellites, and maintaining its own GPS alternative (GLONASS). However, years of underinvestment and Western sanctions have severely undermined Russia’s space program. Its future is now uncertain. The Kremlin’s space agency (Roscosmos) struggles with budget shortfalls and loss of access to Western technology. Notably, sanctions after 2014 (Crimea) and 2022 have cut off Russia from critical components like advanced microchips and satellite electronics, forcing it to delay or downscale space projects. Russia’s heavy-lift rockets (Proton, Angara) face production issues, and its collaboration on the International Space Station will end by 2024–2030, leaving it largely on its own. These trends erode Russia’s ability to field new military satellites or anti-satellite weapons at scale.

Western Europe, meanwhile, has been expanding its own space capabilities, often in concert with allies. The European Union’s Galileo satellite constellation (fully operational in recent years) provides high-precision navigation to European militaries independent of U.S. GPS. Several EU countries – France, Germany, Italy, and others – have modern reconnaissance and communications satellites, giving them an intelligence picture nearly on par with global powers. France, in particular, has a Space Command and is investing in space-based early warning and surveillance. Europe’s commercial space industry (Arianespace and others) continues to develop new launch vehicles, and while there have been delays (e.g., Ariane 6 rocket), the trajectory is upward. NATO as an alliance also declared space an operational domain in 2019 and is setting up a Space Centre, meaning future conflicts would see NATO leveraging members’ combined space assets.

In short, Russia no longer holds a clear superiority in space. Its legacy assets exist – for instance, Moscow still operates military satellites and has tested anti-satellite missiles – but Western countries have caught up in many areas and surpassed in some. Crucially, Russia’s inability to invest at the level of the U.S. or EU means its space infrastructure will continue to atrophy. In a conflict with NATO, Western Europe (with help from the U.S.) would likely enjoy better space-based intelligence and secure communications, while Russia’s satellites could be jammed or even targeted. The playing field in space is gradually tilting away from Moscow, consistent with the broader trend of its declining technological edge.

A walk through Russia’s arsenal reveals a military grappling with obsolescence and attrition. Many of the Kremlin’s key weapons platforms are relics of the Soviet era – some over 40 or 50 years old – that have seen only incremental upgrades. By contrast, Western European forces are built around more modern designs and continue to receive next-generation systems. Nowhere is this contrast starker than in armored warfare. The backbone of Russia’s tank fleet is the T-72, a design from the 1970s, along with a dwindling number of newer T-80s and 90s. After suffering heavy armor losses in Ukraine, Russia resorted to pulling 60-year-old T-62 tanks out of long-term storage and sending them into battle with improvised add-on armor. These T-62s, introduced in 1961 and long retired from front-line units, are markedly inferior to modern Western tanks. (In some cases Russia deployed even older 1950s-era T-54/55 tanks, highlighting the desperation to fill gaps). Western Europe’s armies, on the other hand, field Leopard 2A6/A7 and Challenger 2 tanks, French Leclercs, and soon Leopard 2A8s and upgraded Abrams in countries like Poland – all of which vastly outperform vintage Soviet models in firepower, protection, and sensors. European armor is also supported by cutting-edge anti-tank weapons and drones, making Russian tank assaults extremely costly, as seen in Ukraine.

The same dynamic exists in the air. Russia’s Air Force relies on fighters like the Su-30 and Su-27 variants (designs from the 1980s) and a limited number of more advanced Su-35s and Su-34 bombers. Its purported fifth-generation fighter, the Su-57, exists only in token numbers. By comparison, European NATO states operate fleets of 4-generation fighters (Eurofighter and Rafale) and are collectively acquiring hundreds of F-35 Lightning II stealth jets (600+) – arguably the world’s most advanced multirole aircraft. This generational gap means that in any confrontation, Russian aircraft would be contending with foes that can see and shoot farther. Similarly, many of Russia’s attack helicopters, air defenses, and warships are based on aging designs that lag behind Western equivalents in sensor fusion and precision weapons.

Beyond aging equipment, Russia is grappling with the problem of replacing vast quantities of materiel lost or expended in Ukraine. The war has been enormously costly for Moscow’s arsenal. Independent analyses estimate Russia has lost on the order of 2,000+ tanks, 50+ fixed-wing aircraft, hundreds of artillery pieces, and thousands of armored vehicles in Ukraine – losses it is struggling to replace. Sanctions and limited industrial capacity have forced Russia to ramp up production of Soviet-era designs (e.g. refurbishing old T-72 frames) rather than produce truly modern replacements. Western intelligence assessed in early 2023 that it would take a decade or more for Russia to fully recover from the military losses suffered in Ukraine.

Even a more optimistic estimate by German analysts foresaw 5–8 years needed for Moscow to rebuild its forces to pre-war levels, while some Eastern European officials warn Russia could restore certain capacities in as little as 2–4 years. The range of these predictions is wide, but they agree on one point: Russia cannot rapidly bounce back from the depletion it has inflicted on itself. Any timeframe measured in years (or a decade) is a strategic breathing space for NATO. Western Europe is using that time to rearm and modernize at a pace Russia cannot match.

Furthermore, it is not just about counting tanks or planes; it’s about generating trained units equipped with them. Russia’s mobilization of hundreds of thousands of recruits may refill the ranks on paper, but many are ill-trained and poorly led. Its defense industry, while churning out ammunition and some weapons, “still cannot keep up with battlefield losses” despite being on a war footing. For sophisticated items like advanced missiles, avionics, or electronic warfare gear, Russia’s import dependency is a critical Achilles heel. Western export controls have largely cut off access to high-end microelectronics, meaning any new Russian weapons are likely to be less capable than their Western counterparts or produced in very limited quantities.

In summary, Russia’s military today is a weakened shadow of the force that invaded Ukraine in 2022 – and that force itself proved far less formidable than it looked on paper. Its inventory is both shrinking and aging, with stopgap measures (like repurposed museum-piece tanks) signaling desperation. Replenishing and modernizing that inventory will take many years under the best of circumstances, during which time Western Europe will only widen the gap. For at least the next ten years, Moscow simply lacks the capacity to build up the kind of modern, large-scale army that could challenge NATO in a new invasion of, say, Poland, Romania or the Baltic states.

Russia's new frontline main battle tank in Ukraine. The 60 year old T-62, upgraded with high tech anti-drone cage.

The Drone Warfare Factor: An Isolated Russian Edge

One notable development from the Ukraine war has been Russia’s heavy use of unmanned systems – drones – for reconnaissance and strikes. In this narrow aspect of modern warfare, Russia has shown a degree of innovation and effectiveness that has sometimes outpaced NATO’s peacetime doctrines. On the Ukrainian battlefields, both sides employ large numbers of drones, but Russian forces (often using Iranian-supplied Shahed loitering munitions and a variety of cheap quadcopters) have integrated drones to spot targets for their artillery and to conduct constant harassment of Ukrainian positions. This prolific drone usage has in some ways exceeded what Western armies currently have experience with. A Ukrainian commander observed that NATO militaries are “not ready to resist the cascade of drones” seen in Ukraine. He noted the economic reality: a small $20,000 kamikaze drone can force the expenditure of a $500,000 air-defense missile, a cost exchange that favors the drone user. In 2024 alone, Russia reportedly aimed to produce 1.4 million small FPV (first-person view) drones for battlefield use – an astonishing figure illustrating how central unmanned systems have become to its war effort.

This focus on drone warfare is largely a response to Russia’s other shortcomings (e.g. a lack of precision guided munitions and manned aviation losses). It represents a relative strength for Russia, as NATO countries were not historically investing in swarms of inexpensive drones or loitering munitions to the same extent. Western European armies have some high-end drones (like Reaper or Heron UAVs) but lacked the huge fleets of tactical drones now seen in Ukraine. Recognizing this gap, NATO is rapidly adapting – several European countries are now ordering large numbers of small drones for their forces and developing counter-drone defenses (from electronic jamming to new laser systems). Importantly, Ukraine itself, with NATO support, has innovated with drones, employing them to inflict up to 80% of Russian battlefield casualties in some cases. Western militaries are absorbing these lessons. The “drone gap” is closing as NATO standardizes tactics for drone swarms and hardens its units against them.

Thus, while Russia’s competency in drone warfare is notable, it remains an isolated advantage. Drones alone cannot win a war or overcome the vast deficiencies Russia faces in other areas. They are a tool – one that NATO can counter with the right mix of technology and tactics. If Russian forces were to rely on drones to offset their weaknesses in a fight against Western Europe, they would soon find NATO pilots and air defenses wiping those drones from the sky. Indeed, Ukraine has demonstrated that with robust jamming and newer anti-drone methods (from electronic warfare to portable interceptors and lasers that can burn through optical fibre cables), the impact of Russian drones can be blunted. In sum, unmanned systems are a domain to take seriously and invest in (Western defense planners are doing so), but they do not fundamentally alter the balance of power that tilts strongly in NATO’s favor.

A Ukrainian drone production facility. Russia has the edge over NATO in experience using drones, but Ukraine has matched it, and can show NATO the way, if NATO leaders are smart enough to follow.

Economic Power and Defense Industrial Capacity

At this moment it is instructive to remember the Cold War with the former Soviet Union was won not by numbers of missiles, but by the collapse of the ruble.

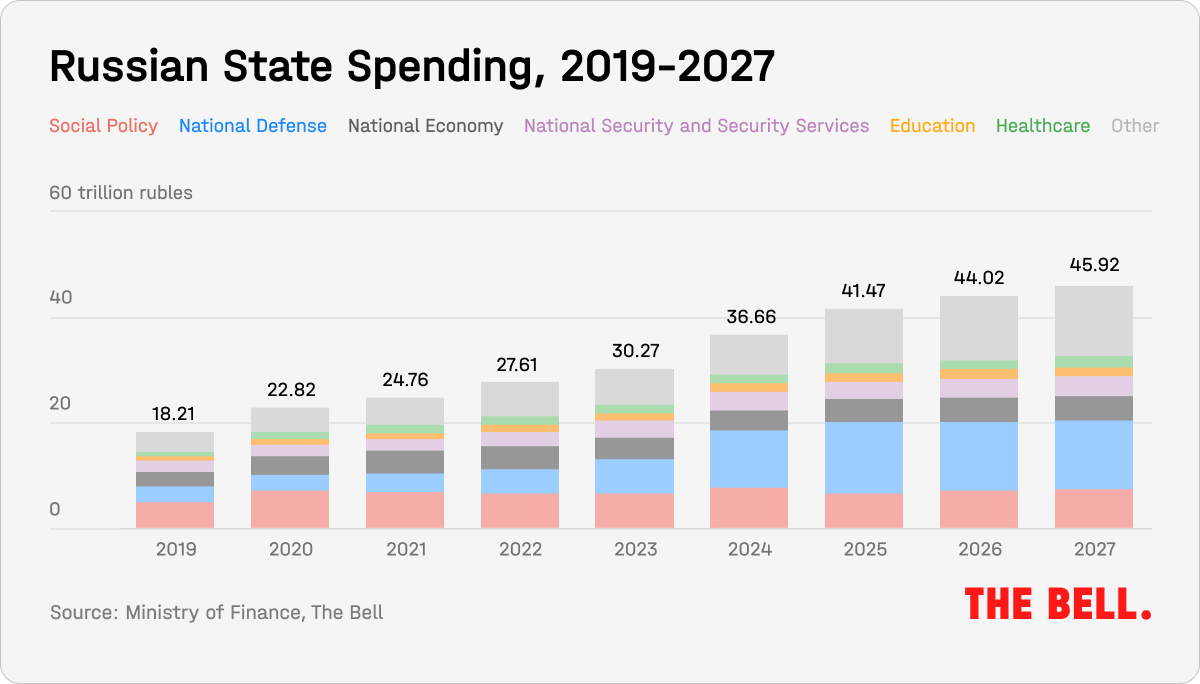

Military strength is ultimately underwritten by economic strength – and here Western Europe’s dominance over Russia is unequivocal. The combined GDP of the European Union (most of whose members are in NATO) is on the order of $16–18 trillion, roughly ten times larger than Russia’s GDP (approximately $1.7–2 trillion) in the mid-2020s. This immense economic base means Western European nations have far greater ability to finance defense and absorb the costs of long-term competition. Even after massive sanctions and war-related shocks, Russia has been pouring as much as 6–7% of its GDP into military spending to keep up the fight – an unsustainable burden for a middling economy. In 2024, Russia’s defense budget surged to an estimated ₽13.1 trillion (about $146 billion), consuming a huge share of national resources. Western European NATO members, by contrast, still mostly spend around 2% of their far larger GDP on defense (though many are now increasing toward 2.5% or more). Germany, France, and Italy – Europe’s biggest economies – each have GDPs comparable to or larger than Russia’s, yet are only beginning to ramp up defense budgets after years of underspending. They have ample fiscal room to grow. For instance, Germany’s historic €100 billion defense fund (announced in 2022) and France’s multi-year military spending boost will, over time, dwarf anything Russia can allocate without wrecking its economy.

In terms of raw defense expenditure, Europe’s collective military spending vastly exceeds Russia’s. An authoritative 2025 study by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) found that Europe’s combined defense spending for 2024 was about $457 billion – roughly three times Russia’s nominal military budget. Even when adjusting for purchasing power parity (to account for Russia’s lower costs), Russia’s war-fueled spending (estimated ~$462 billion PPP in 2024) only barely matches Europe’s in effective terms. And Europe is not standing still: 2024 saw an 11.7% real increase in European defense spending, the fastest growth since the Cold War. Western European countries are investing in new factories for ammunition, new shipbuilding programs, next-generation fighter development (the Franco-German-Spanish FCAS and Britain’s Tempest), and other big-ticket projects, many accelerated by the wake-up call of Ukraine. In a protracted competition, Russia cannot win an economic contest with the combined West. Its economy is simply too small and too dependent on energy exports, which are volatile and increasingly sanctioned. By contrast, the diversified, high-tech economies of Europe can sustain and surge defense output as needed – from precision missiles to semiconductors – especially when pooling efforts through EU and NATO frameworks.

Industrial output is another facet of this strength. Western Europe possesses a sophisticated defense-industrial base capable of producing everything from nuclear submarines to advanced jet engines. Factories across Europe are now running at heightened tempo to replenish stocks (for example, producing artillery shells for Ukraine and for their own reserves). While Russia has tried to surge its military-industrial output by adding shifts and mobilizing labor, it faces critical bottlenecks – lacking certain machine tools, relying on antiquated plants, and having lost access to Western suppliers. According to one analysis, Russia’s military industry “still cannot keep up with battlefield losses” despite high wartime spending. In the long run, Moscow’s ability to field state-of-the-art hardware will erode further if it cannot import advanced components; whereas Europe (with the U.S. as an ally) can tap global supply chains or develop domestic alternatives.

Ultimately, Western Europe’s financial and industrial clout means it can outlast and out-produce Russia in any arms race or military confrontation. NATO’s own Secretary General (and European defense officials) have acknowledged that while Russia is not to be underestimated, the West’s latent power greatly exceeds Russia’s, provided it is harnessed. Recent warnings – such as a Danish intelligence report suggesting Russia could be ready for “large-scale war” again in five years – are actually intended to spur Europe to expedite its rearmament. The reality is that Europe has the money and technology to do so. In contrast, Russia is spending a huge portion of a much smaller pie and burning through its military capital for marginal gains. This imbalance in economic stamina means that Western Europe can confidently plan its security knowing Moscow cannot afford a sustained showdown. Should Russia somehow attempt one, it would risk economic collapse on the home front long before Western Europe ran out of resources to defend itself.

Lessons from Russia’s Failures in Ukraine

Perhaps the most compelling evidence that Russia is not a serious threat to NATO Europe in the near future comes from Russia’s own performance in Ukraine. The invasion launched in February 2022 was supposed to overrun Ukraine in a matter of weeks – instead, it has bogged down for over three years with devastating consequences for Russian forces. The Kremlin failed in its attempt to achieve a quick victory and has since been forced into a grueling war of attrition against a far smaller adversary. If Russia cannot decisively defeat Ukraine – a single non-NATO country with a fraction of NATO’s capabilities (albeit bolstered by Western aid) – it is hard to imagine it posing a credible offensive threat against the combined strength of Western Europe.

The war has exposed fundamental weaknesses in Russia’s military. Poor planning and logistics plagued the initial multi-front invasion. Long convoys stalled out from lack of fuel and maintenance; units advancing toward Kyiv outran their supply lines and had to retreat. Russia dramatically underestimated Ukrainian resistance and overestimated its own capacity to sustain high-tempo operations. According to a detailed RAND study, Russia did not have the logistical force structure needed for its ambitious plans, and once the invasion met serious opposition, the entire enterprise faltered. These problems were not just early mishaps – they have persisted. Throughout 2022 and 2023, Russian units were hampered by basic supply shortages, inadequate trucking, and a lack of secure communications. Maintenance failures and a shortage of spare parts sidelined many vehicles. The vaunted Russian army, it turned out, could not effectively execute combined-arms maneuvers at scale. In contrast, NATO militaries place heavy emphasis on logistics, professional NCO corps, and joint operations – areas where Russia revealed itself to be “barely competent at best”.

Russia’s battlefield setbacks underscore these shortcomings. In spring 2022, Russian forces were beaten back from Kyiv and Kharkiv. Later that year, they had to abandon Kherson city in the south under Ukrainian pressure. In 2023, Russia launched a winter offensive in the Donbas that yielded only “modest territorial gains” and at great cost. The capture of Bakhmut – a small city – took nine months of bloody fighting and tens of thousands of casualties, only for Russia to end up on the defensive soon after. By early 2024, neither side was making dramatic breakthroughs, but notably Russia was unable to exploit its numerical mobilization to conquer significant new territory. Every Russian advance has been slow and limited, while Ukrainian counteroffensives (aided by Western weapons) have punched through Russian lines in places like Kharkiv Oblast. This pattern suggests that Russia lacks the offensive punch and coordination to prevail against a determined, well-armed defender. If that defender were NATO – with far superior air power and deep reserves – Russia’s prospects would be near hopeless in a conventional fight.

Moreover, the Ukraine war revealed a Russian military plagued by morale and leadership issues. Large portions of the fighting have been carried by hastily mobilized reservists, prison conscripts (in the Wagner mercenary group), and ethnic minority units – many of whom are poorly motivated. Command hierarchies have been in flux, with frequent reshuffling of generals and public infighting between the Defense Ministry and mercenary leaders (as seen in the Wagner mutiny episode). This is not a force that can take on a unified, professional NATO force. Russia’s inability to effectively coordinate air support, electronic warfare, and ground maneuver in Ukraine has been a glaring vulnerability. NATO doctrine excels in precisely these areas, integrating all branches to overwhelm adversaries. In essence, Ukraine has been a live-fire test of Russia’s military – and the results have largely debunked the notion that it is a peer, let alone superior, to Western forces.

To be sure, the Russian military has adapted in some ways during the conflict – for example, improving trench fortifications and learning to use drones – but these adaptations are mostly tactical tweaks, not a transformation into a new, more dangerous force. As Al Jazeera’s defense correspondent observed, Russia’s armed forces have been exposed as “barely competent,” showing only minor improvements that don’t change the overall picture. “Russia is in no shape to take on NATO,” he concluded bluntly. The risk, if any, is that Moscow might resort to nuclear escalation if faced with total conventional defeat – but Russia’s leadership knows that initiating a nuclear war against NATO would be suicidal. Nuclear saber-rattling thus remains rhetorical. In conventional terms, Europe can take confidence from the fact that the Russian military machine has been largely humbled in Ukraine. There will be no repeat of lightning Soviet blitzkriegs into the heart of Europe; those days (if they ever existed) are long gone.

Given all the evidence that Russia is a diminished conventional threat to Western Europe, why do some European leaders continue to sound alarms about Moscow? The answer lies partly in domestic politics and strategic incentives. Highlighting the Russian threat can serve multiple purposes for NATO-aligned governments – from justifying defense investments to diverting public attention from internal issues. Experts have noted that certain European countries may be “exaggerating perceived security threats” in order to prepare their publics for worst-case scenarios and rally support. There is often a fine line between prudent vigilance and threat inflation, and politicians sometimes err on the side of dramatizing dangers for their own ends.

One motivation is to justify major new investments in defense industries. After decades of post-Cold War military austerity, many Western European nations are now ramping up defense spending. This often requires selling the public (and parliaments) on why such spending is urgent. Citing a menacing Russia – one that might one day attack NATO territory – is an effective rationale. For instance, Sweden’s government, ahead of joining NATO, explicitly labeled Russia a “principal threat” and stated “the risk of an attack cannot be excluded,” as it boosted defense outlays to 2.4% of GDP. Such language helps unlock budgets for new fighter jets, tanks, and warships. It also aligns with the interests of domestic defense contractors, who stand to gain from increased orders. As a 2018 analysis wryly observed, one might conclude that “the threat from Russia is being grotesquely exaggerated” by those who are “promoting their own commercial or political interests.”

Defense companies and their political backers have incentives to paint a dark picture of external threats to ensure steady funding – a modern echo of the old “military-industrial complex” dynamic. In Europe’s case, investing in defense can also create jobs and spur technological innovation, a fact not lost on leaders eager to stimulate growth. Big procurement programs often come with regional employment benefits, which makes them politically attractive. In short, a perceived Russian threat provides convenient political cover for rearming – something that may be necessary anyway, but is made more palatable when there is a villain to point to.

Another reason for emphasizing the Russian menace is to forge unity and distract from internal problems. Leaders facing domestic discontent – economic woes, protests, political polarization – may invoke external threats to foster a “rally-around-the-flag” effect. External danger can deflect criticism and encourage citizens to support their government. In the EU, invoking solidarity against Russia also reinforces cohesion among member states and with the transatlantic alliance. It is no secret that public support for NATO shot up after the Ukraine invasion; politicians naturally lean into that narrative of a common foe. Some analysts have gone so far as to call much of Putin’s bluster “just rhetoric” that European leaders publicly downplay, even as they quietly use it to bolster their agendas at home. For example, when Putin threatened that NATO was at war by assisting Ukraine, many European officials shrugged it off as empty talk. Yet those same officials often stress to their constituents that Russia must be deterred at all costs – a dual messaging that manages the risk without letting a good crisis go to waste.

To be clear, none of this is to suggest that European governments do not genuinely perceive Russia as a potential danger; rather, it’s that the scale and immediacy of the threat can be exaggerated for effect. Take, for instance, the dire warnings that Russia might attack NATO in a few years if we don’t act now. These warnings (such as the Danish intelligence claim of a possible “large-scale war” by 2030) serve to keep publics alert and supportive of defense readiness. However, independent experts often push back on panic. “Russia has made no military deployments to threaten Finland or Sweden… given the way the Russian army is tied down in Ukraine, the very idea is absurd,” observed one security analyst when Nordic countries issued war preparedness booklets. This underscores that some measures – distributing survival guides or talking up invasion risks – may be more about instilling vigilance than responding to any real near-term likelihood of attack. In essence, European leaders might inflate the Russian threat because it is geopolitically convenient: it reinforces alliance unity, secures defense funding, and channels public anxiety toward an external object instead of domestic failings.

Finally, one cannot ignore that there is a genuine strategic logic for Europe to not become complacent. By talking tough and preparing for the worst, NATO’s deterrence is strengthened, which in theory reduces the chance of Russian miscalculation. The unfortunate flip side is that this necessary caution can spill into public discourse as alarmism. The key is to strike a balance – neither naive about Russia’s aggressive potential nor hysterical about its capabilities. At times, some in Europe lean toward the latter, using Moscow as a convenient scapegoat or fear factor to achieve short-term aims. But as this analysis has shown, the underlying fundamentals favor Western Europe quite heavily.

In sum, the evidence strongly supports the claim that Western Europe has little to fear from Russia over the next decade. Barring some drastic, unforeseen change in Moscow’s trajectory, Russia simply lacks the means to challenge NATO Europe in any meaningful way. Three key reasons stand out:

- Military Overmatch: NATO’s European members (even without the U.S. and U.K.) enjoy an overwhelming superiority in conventional forces – more troops, more tanks and aircraft, and far more modern weaponry than Russia can bring to bear. Decades of development mean Western Europe holds the qualitative high ground in training, technology, and integration of forces. Russia’s army, by contrast, has been bloodied and diminished in Ukraine and relies on aging equipment that would fare poorly against advanced Western systems. In any direct conflict, NATO-Europe would outmatch and outmaneuver Russian forces from the outset, ensuring defense of its territory.

- Economic & Industrial Dominance: Western Europe’s economic might and industrial base far exceed Russia’s, granting a sustained advantage in any long-term competition. Europe collectively spends on defense at levels Russia cannot afford without crippling itself. Its factories can out-produce Russia’s in everything from missiles to tanks, especially as peacetime industries convert to defense output when needed. Meanwhile, sanctions and the strains of war have hollowed out Russia’s high-tech sectors, leaving it struggling to replace losses. Over the next ten years, Western Europe can easily maintain a pace of rearmament and technological advancement that Russia’s stagnating economy cannot keep up with, ensuring NATO retains a decisive edge.

- Russian Weakness and Containment: Russia has demonstrated profound military shortcomings – poor logistics, ineffective leadership, and limited power projection – through its failure to achieve objectives in Ukraine. Its forces are tied down, its arsenal depleted, and its geopolitical position weakened (with NATO expanding to Finland and Sweden, further containing Russia’s reach). Simply put, Moscow lacks the capacity to launch or sustain an invasion against any NATO country. European experts note that Russia has made no concrete moves that would indicate preparations to attack the EU/NATO, and the notion is “absurd” given its entanglement in Ukraine. Nuclear threats aside (which remain extremely unlikely to be acted upon), Russia’s conventional military will remain a regional nuisance at best, not an existential danger to Western Europe.

In light of these points, Western Europe can approach the coming decade with confidence. Vigilance and prudent defense preparations are always wise – and Europe will rightly continue supporting Ukraine and fortifying NATO’s eastern flank – but there is no need for fear or panic regarding a Russian assault on Paris, Berlin, or Rome. The balance of power is firmly on Europe’s side. In fact, Europe’s biggest challenge may be managing its own unity and political will, rather than anything Russia can throw at it. As long as NATO-Europe stays cohesive and continues leveraging its vast resources, Russia will remain deterred and incapable of serious aggression westward.

The “Russian threat,” in the context of Western Europe, is thus largely a bogeyman – one that grabs headlines and budget euros, but in reality, lacks the claws to match its roar. Western Europe’s security for the next ten years, and likely well beyond, is assured by its collective strength, leaving the Kremlin little choice but to back down from any direct military confrontation.

(AI disclosure: this article was researched with the aid of Chat GPT.)